Name: Ivy

Location: New Hampshire

I watched a lot of towns in southern New Hampshire zone themselves out of existence.

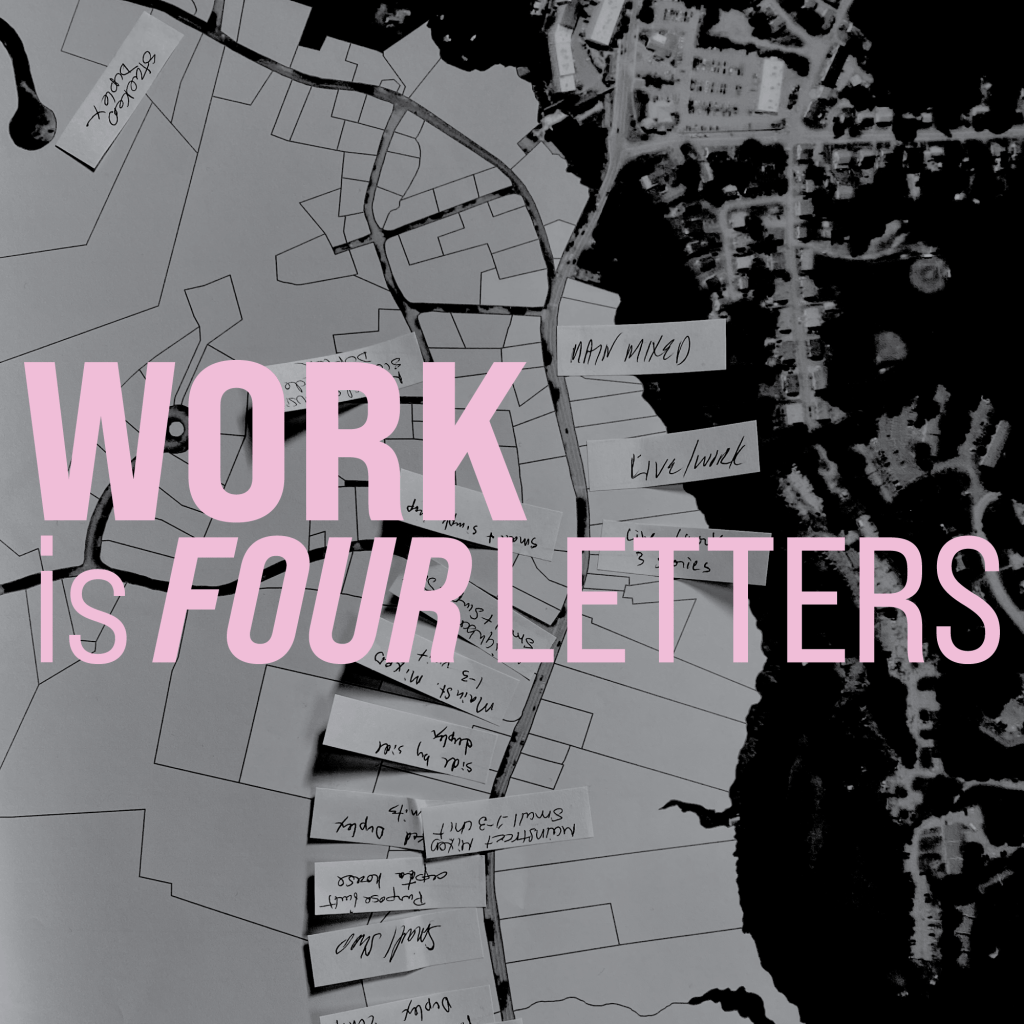

I am technically known as an urban planner. I specialize in helping smaller places do two things: I help them figure out why they’re not getting the built environment that they want. Spoiler: it’s your zoning. I do a lot of work around housing choice and availability. Zoning is not the answer to everything, but it is part of the answer to everything.

This is my fifth career. I went back to the college from which I graduated, today, to take a class, and it was kind of stunning. It was a library when I was there, and I realized as I walked up the steps: I first walked these stairs about 50 years ago. In the interim, I have done a bunch of different things. I was a children’s librarian for 3 or 4 years. From there, I went to work for a small town weekly in southern New Hampshire. Eventually I was a section editor, the editor for the town section. That’s not the first place I started thinking about the built environment, but it’s one of the first places that I started thinking “Why do we build such shit when we have great examples in front of us?”

I watched a lot of towns in southern New Hampshire zone themselves out of existence. They panicked about people with children moving to town, because everything, all the education in New Hampshire, is funded on the back of the local property tax. No income tax. No broad-based tax. Just property tax. They’re this cute little town and they want to stay that way. So, they enacted 3- and 5- and 7-acre zoning, which meant that you had to have a big parcel of land. What that did was make their existing village illegal and irreproducible. You had to have 3 acres per house. A typical village lot is in the neighborhood of 5000ft², 7500ft². That’s 1/8 of an acre. If you’re requiring a 3-acre minimum, you are requiring 24 times as much land for a single family house as you have in your village.

I didn’t have the language to talk about it back then, but you end up with suburban sprawl. Big box stores with giant parking lots. Villages that were beautiful and walkable and had a little village store — their property values there always stayed high, even in the crash of 2008, even in the crash in 1988. I’m so old, I remember when those areas held their value, because there weren’t very many of them. If you look at Philadelphia, Park Slope, you’ve got these places that work well as habitats for humans, but you can’t build new ones because you’ve adopted this idiotic zoning. There are places that have beautiful, walkable, human-scaled character with corner stores, but you can’t build any more of them.

I’m trying to teach people how to allow that development form to return.

I was a reporter, then I went to seminary, then I raised 4 children, and then I got a master’s in education and taught. My husband and I were living in a rental house and trying to find a house to buy, and we couldn’t find anything. I said to my husband, “Well, we could build a house”. He said, “Yeah, we did that once”. I said, “Yes, and look, we’re still married! We did it! It was fine, and we could do it again”. The next day, I was talking to a friend who’s an environmental engineer, and I said, “Have you run across a building lot in Peterborough?”, where we were living, and he said,”You wouldn’t want to live on High Street, would you?” I was like, sarcastically, “Oh no, Richard, I would never want to live on High Street”. I didn’t realize there was a lot on High Street, and technically there wasn’t. But there were 23 acres of land, which is a big chunk of land, and it had access off of High Street, which was and is a very nice neighborhood.

On New Year’s Day I walked the land with a friend on the conservation commission, and he said to me, “Ivy, I think you need to build a neighborhood here”. He said “Halloween should be your model”. I now know that there is a thing called the Halloween model, which tells you that your neighborhood is successful if you have a rip-roaring Halloween trick-or-treat parade, because what that means is the houses are close enough together so that the kids can walk from house to house and the parents can trail along behind. That neighborhood that has the best trick or treating in your town. That’s your model for what you should be building. I went home that night and said to my husband “Our friend says we ought to build a neighborhood on that parcel”. He was like, “I do not have time to take on another project. I have a business”. The next day at dinner time, we sat down and he looked at me and said, “I’ve been thinking about that neighborhood, if there were someone with a not too demanding day job…”, and I was working as a nursery school assistant at the time. So it became my project.

What I do is a combination of translation and evangelism. I explain why your place looks the way it does and what you can do to make it look different. That’s the translation. I’m trying to convince you that this is a good idea. That’s the evangelism.

I went to Florida for a 4-day workshop on building the new traditional neighborhood, and I discovered that I was a New Urbanist. I had no idea until I showed up there, but I had been this my whole life. All the things they cared about were all the things that I cared about. People were so generous, and so kind, and so helpful, and they said, “You can do this. You can build a neighborhood”. So I hired a New Urbanist firm.

We drew up beautiful plans to build this new neighborhood on High Street, where you have all the things that we wanted and short frontages and walkable streets on Halloween. Then, I ran smack up against the zoning code, which required 75 feet of frontage. You can’t build a neighborhood like that. We messed around for a couple of years. We tried using a code that allows you to manipulate your lot sizes, but it requires you to throw away half the land. In the end, the crash of 2008 happened and the bottom fell out of the market.

We never built anything. I sat on the land for 18 years. In the meantime, I got myself onto the planning board. I started going to conferences and taking classes and doing the reading and talking to people, and then I took the exam, and I became a certified planner. What I do is a combination of translation and evangelism. I explain why your place looks the way it does and what you can do to make it look different. That’s the translation. I’m trying to convince you that this is a good idea. That’s the evangelism.

My first job once I got certified was for the Congress For the New Urbanism as a project manager, on a project that they were running all across the country with the American Association of Retired People, who, by the way, are big proponents of good development. They have done a lot towards making walkability something that we can talk about without freaking out. It’s going to be a huge problem as the United States ages — we’ve got a lot of people in their 60s and 70s who are still living in suburbia. If you cannot drive and you live in suburbia, it’s a bad scene.

I want you to care about those people who aren’t here.

Here’s the thing: we need statewide reform, because there’s really nothing in it for 1 town to do the right thing if the other towns around it are not, why should 1 town say, “Okay, we’re going to legalize up to 4 units on any lot”, if the town next door is like,”No, we’re sitting with our 2-acre zoning”. It doesn’t make sense.

What I talk with these towns about is that nearly every town has a village center. What I try to convince them is, okay, you can require giant lots out in the rural district. That’s fine. We can talk about the road costs, but that’s not a terrible thing. But you have to allow a more historically appropriate pattern somewhere. You need to lean into your village, you need to replicate your village. There are ways of dealing with water and sewage and septic that will allow you to have closer lots.

I come from a long line of storytellers. If you take a group of people who showed up at a meeting, they’re cranky when they get there because they’re pretty sure that somebody is trying to put something over on them. I send out postcards that say, “Come to housing camp, we’re going to talk about housing issues facing your town!”, and then I go check the local Facebook page to see what’s going on. Sometimes, they’re convinced it’s a communist plot, and that all these housing units that we’re talking about are there to house illegal aliens. And also, that I hate their pickup trucks. That actually is true. I do hate their pickup trucks.

But what I’m trying to do is tell a story and help them tell their stories to each other about their lives and their housing situation. I want them to talk to the people at their table, and I want them to tell their stories, and I want them to tell the stories of people who aren’t in the room. I want you to care about those people who aren’t here.

I served 4 terms in the New Hampshire House. Do you know anything about the New Hampshire House? It is the third-largest English-speaking legislative body in the world. After the House of Commons and the US House of Representatives, the New Hampshire House has 400 members. For every 3200 people, you have a rep. My town has 6400 people. We have 2. You can’t get anything done, every term, the turnover is just punishing. Something like 1/3 of the House turns over every 2 years. You constantly get new people who don’t know anything about how anything works. Also, they pay you $200 and they take out federal taxes. I told somebody the other day, it’s not even enough to buy a pair of fancy shoes.

Of the jobs I’ve ever had, or all the careers I’ve ever had, or even the jobs I ever wanted, they all had that storytelling piece. I taught everything, but I loved teaching history because that’s storytelling. I went to seminary, that’s nothing but storytelling. They are what makes us who we are, the stories that we tell about ourselves.

I see this a lot right now, because the housing market is so tight everywhere — everybody is looking for a villain, right? The latest is Blackrock. Blackrock is coming to your neighborhood to buy all the houses, they’ll inflate the prices and not maintain them. But that model only works if your place is already undervalued. Memphis. Southeast Atlanta. Jacksonville, Florida, all of those places, those neighborhoods that have been underinvested in, and that are primarily occupied by black and brown folks, those places are ripe for that model. But in most places, that’s not your villain. The villain is you.

Our zoning codes make our places worse. I’d like to see an understanding that if we hope to have adequate housing choice, adequate housing availability, adequate housing attainability, we have to allow more housing to be built, across the board. We just haven’t built enough and we haven’t built the right things. We’ve privileged 2 things: big, single family houses on lots out by the edge of town, and 40-unit garden apartment complexes out by the highway. Those are the only things we built in most places for the last 50 years. We need to go back to building actual places.